In 1979, the Ute Press published the Preliminary Edition of the Ute Dictionary written by then Director of the Ute Language Program, Tom Givon with the help of many tribal elders and those within the Ute Language Committee. The Dictionary was just one vital step towards working to preserve the Ute language. Former Tribal Chairman Leonard C. Burch contributed to the dictionary by providing the foreword which detailed the mission of the book, the importance of learning the Ute language, and the mission of the Ute Language Program established in the 1970s.

“Our language had been retreating slowly, our young people had ceased to learn and use it,” Chairman Burch wrote. “Unless something was done soon, we felt, the Ute language was in grave danger of disappearing from the face of the earth…If we are to remain Ute, we must protect our language from dying out, we must help it regain its rightful place in our lives, and in the minds of our people, especially our young.”

Creating SILDI

40 years later, in 2019, the Southern Ute Tribe continued its mission to help revitalize the Ute language through an order from the Tribal Council under Chairman Christine Sage and the Executive Office. The Southern Ute Education Department began the process to conduct a survey with the help of Southern Ute tribal elder, Lynda D’Wolf to discuss the importance of the Ute language with elders and fluent speakers of the Ute language. They found that the Ute language was at a critical level with an estimated 30 fluent speakers remaining in the Southern Ute Tribe.

“When we first started, I got Dr. Lynda D’Wolf, and we went door knocking to talk to the elders,” Education Director LaTitia Taylor said. “We started telling them about this [grant] and ask what they would like to see out of this. Then we had some focus sessions with some Ute Mountain and Southern Ute elders. We accumulated all of this [information].” With the data gathered, the grant was written in collaboration with the Culture Department Director Shelly Thompson, and staff members from the Education Department. With the aid of Dr. Stacey Oberly, Ute Language Coordinator for the Southern Ute Indian Montessori Academy (SUIMA), a Ute language curriculum was created as part of the application of the grant.

The three-year grant was awarded in 2021 by the Administration for Native Americans (ANA) Preservation and Maintenance and helped create what was known as the UTE (Using Technology and Education) Language Preservation Project. Three tasks were introduced within the parameters of the grant. The tasks were to create the Southwest Indigenous Language Development Institute (SILDI), certify at least 15 Ute community members to teach the language under the SILDI program, and create an audio and video dictionary application for the Southern Ute membership and SUIMA classrooms.

“We have to learn the language through the formal education; there has to be apps; elders have to be interviewed,” Taylor said about the program and the grant. “We had the Education and Culture Departments working to get it done. I think it was a success.”

By 2021, classes began for the certification, and students would work intensively to learn both the Ute language and teaching methods for the next two and a half years.

Learning to teach Núu-‘apaha-pi

Fort Lewis College is a partner in the program and works in collaboration with the Tribe’s Culture and Education Departments to help students of the SILDI program receive their accreditation. The classes feature a unique synchronized learning of both the Southern Ute dialect of the Ute language and an enhanced component learning how to teach the language. The college is working closely with the Colorado Department of Education to allow those completing the program to receive an adjunct faculty license which allows for the students to teach at public schools within the state.

At first, the program aimed to help teachers at the Southern Ute Indian Montessori Academy (SUIMA) to become Ute language instructors and was open to the Southern Ute membership. Later the program was opened to members of the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe and Ute Indian Tribe. Over 100 individuals from all three tribes were interested in the program and 32 participants started the program. 27 students completed the class and earned their certificate Friday, May 5 during a commencement ceremony at Fort Lewis College.

“The program has a 90 percent retention rate which is really high for classes on Saturday and in the summer,” Dean of the School of Education at Fort Lewis College, Dr. Jenni Trujillo said. “It is a really amazing resilience and stamina that the students have shown working that long to complete a program that long.”

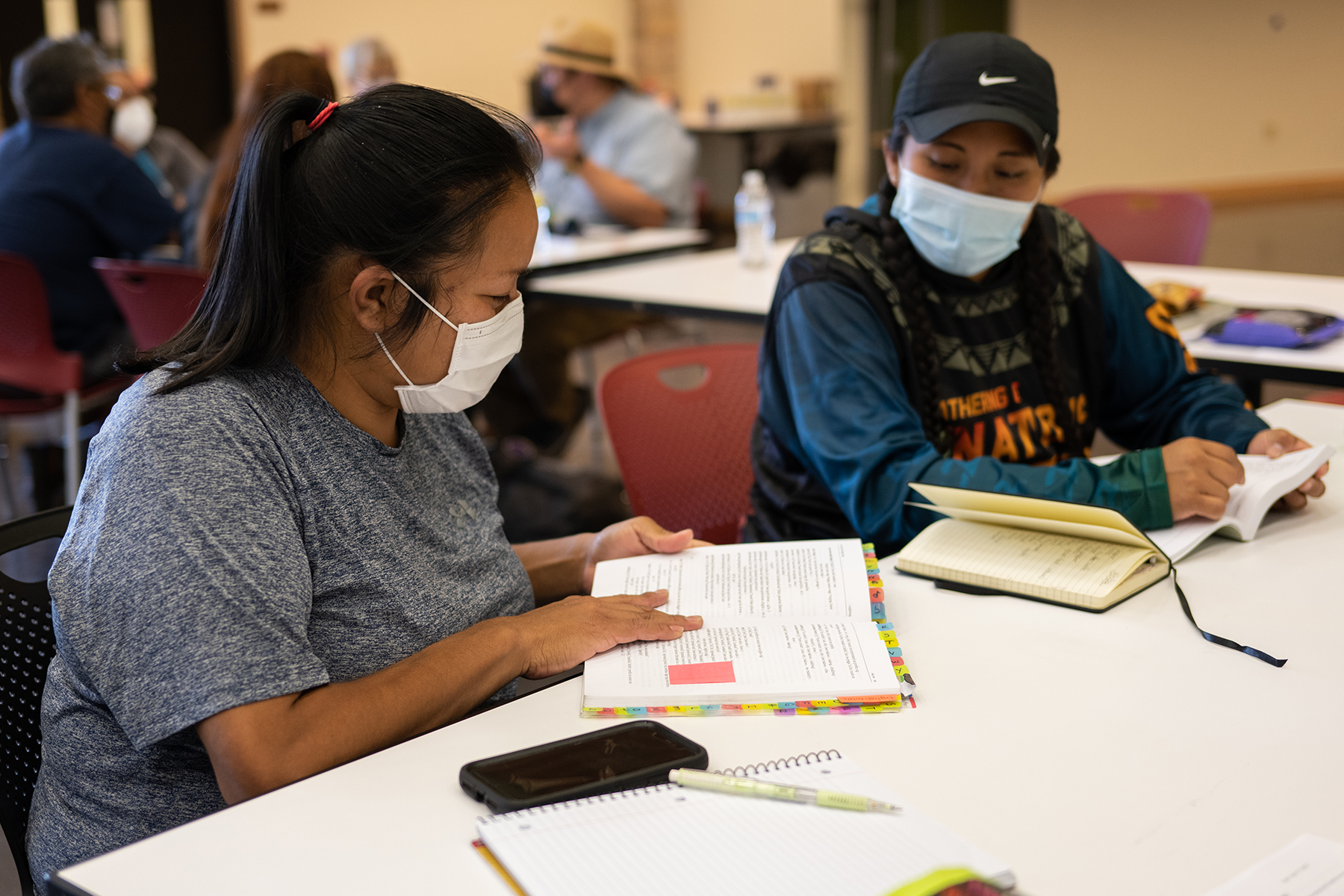

The intensive two and half year program consisted of 10 classes and 30 credits in a hybrid online and in–person environment to accommodate the COVID–19 Pandemic and those living longer distances. Cohorts met during the weeks and during summers, with many students holding full-time jobs and other commitments outside of the classes.

“Each class required an in-person session, usually at the beginning and end of the class,” Culture Department Director, Crystal Rizzo explained. “We would all come together for a weekend and spend a chunk of time doing cultural programing, language programing, class work.”

Students were also required to perform quarterly reports on their work within the class to help show their increase in language proficiency. According to Dr. Trujillo, the goal was to increase by one level in language proficiency and was based entirely on the individual person. The program itself was not designed to have an individual become fluent but to increase their understanding of the language by one level.

“There are five levels of language proficiency, and we agreed to try to increase by one,” Dr Trujillo explained. “So, each person, even if you just develop receptive language, or people who could say nouns and name things, could they begin to say phrases or could they begin to know the morphology of the language and the syntax…Our goal was to just increase by one language level.”

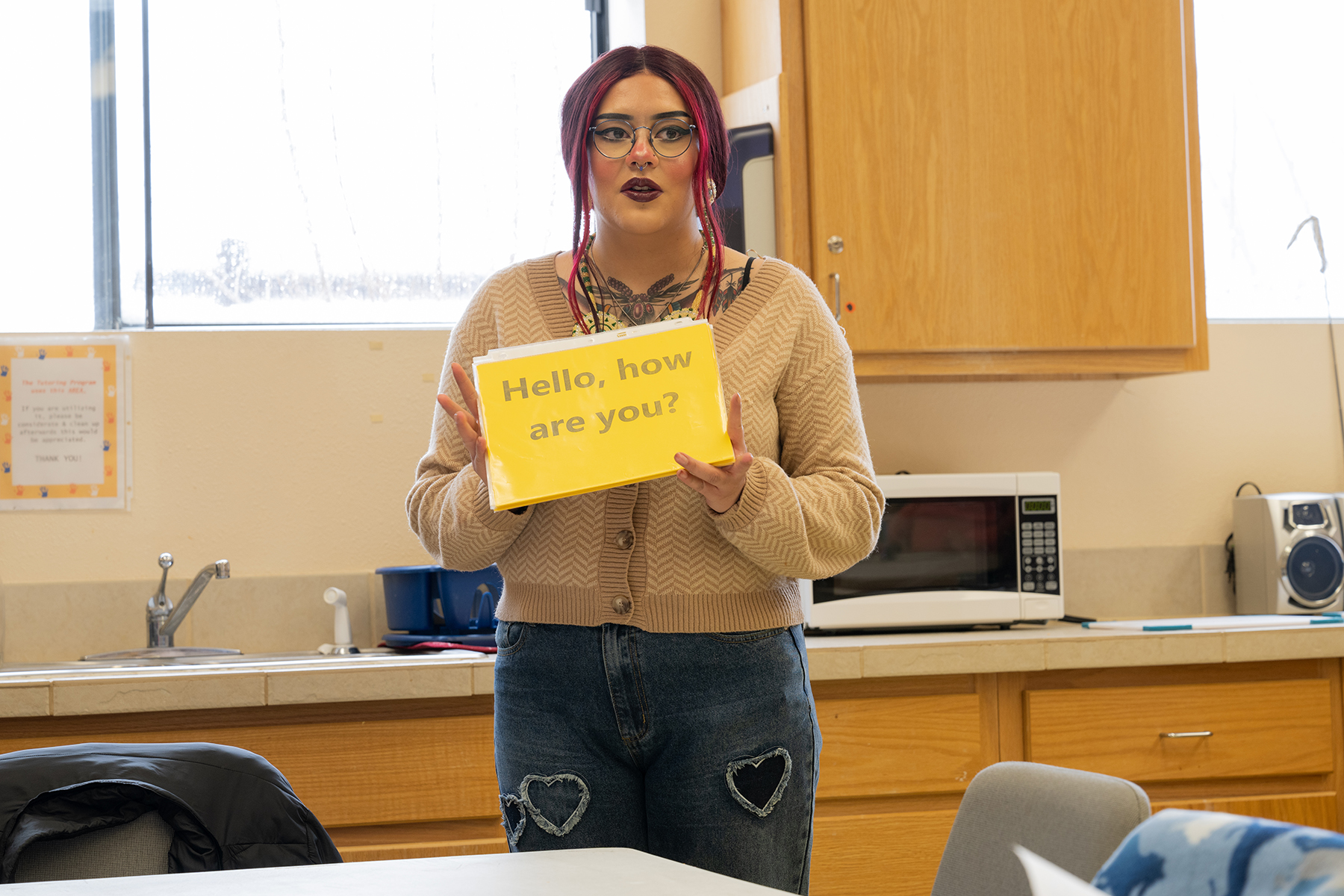

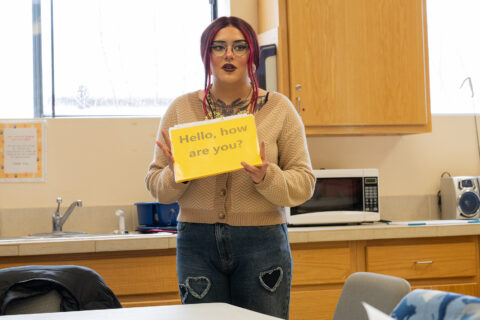

The end of the program featured an opportunity for students to receive experience teaching the Ute language classes in a public setting, as required by the program.

“Once we understood as teachers what the terminology, and the different techniques and styles of teaching that is when the Ute [language] part came in,” SILDI student Izabella Cloud said. “After all of the academic stuff, then started to apply that to letting us teach.” Cloud explained that in the final part of the program, they prepared a curriculum and lesson plan relating to the Ute language and whichever way they would want to approach and teach the language. “In my mind, I don’t think learning ever stops. I don’t think the certification is a one and done thing.”

Finding community through language

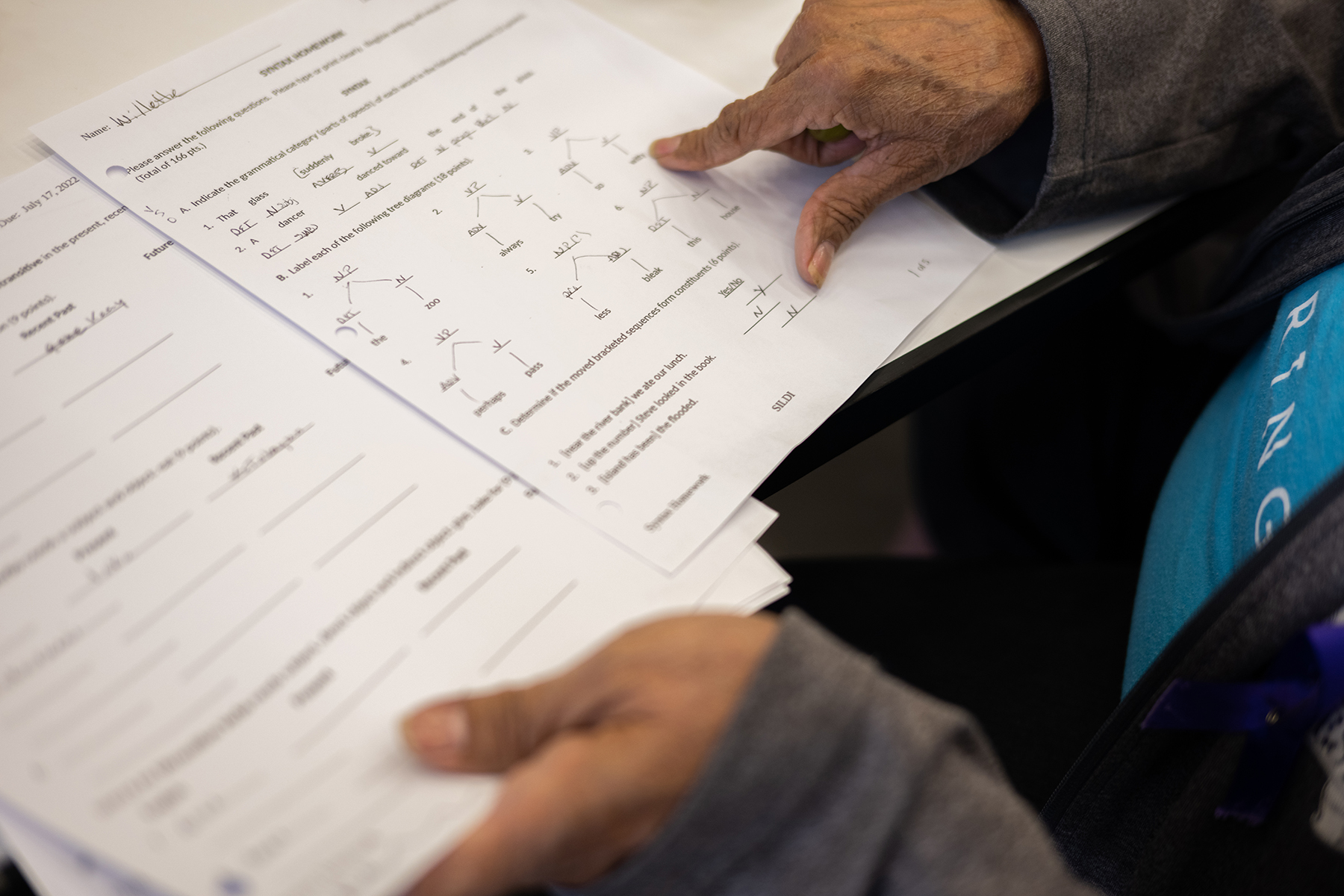

Southwest Indigenous Language Development Institute (SILDI) students met with education instructors, instructors specialized in linguistics, and elders fluent in the Ute language to learn methods to teach. Students were also able to learn the Southern Ute Dialect with the aid of the “Givon” Ute Dictionary and Reference Grammar texts. Students supplemented their learning of the Ute language with the help of fluent Southern Ute elders and the mentor circle. Such Ute language aids were former Southern Ute Chairman and tribal elder, Pearl Casias; tribal elder, Judy Lansing; tribal elder, Dorothy Wing; and SUIMA Ute Language Guide, Shawna Steffler. Other aids in the mentor circle included past instructors from the courses, staff from the Southern Ute Indian Montessori Acadamy (SUIMA), and the Southern Ute Education Department.

“It was really useful for elders to check in and observe,” Rizzo said. Some Elders were asked to give feedback, grading, and guidance which guide the program. “I think that it was really important to ensure that the elders’ opinions and voices were heard in this process. I think that even changed some of the way in the second half of the program how we structured things was a bit from elders saying, ‘these are things you guys need to be doing to make sure this is done the right way.’”

Students were able to talk with those in the mentor circle and ask one-on-one questions on pronunciation, grammar, and syntax. The mentor circle established in the SILDI program helped create an environment where the students and teachers could support students and allowed them to make mistakes and learn from those who were fluent in the language.

“Language is a lot of work, because it comes with criticism; it come with encouragement; it comes with ‘Am I doing this right, am I teaching this right?’ SILDI student Daisy Blue Star said. “I think through SILDI and the support that we all have for each other, to me that’s a safe zone, because I know we are all learning. SILDI has pushed us through to not being scared.”

Many used the mentor circle to learn higher levels of understanding within the Ute language that would not be learned in a textbook.

“Ute was not spoken English to Ute. I noticed when you speak from Ute to English your English is messed up. In Ute, you say it backwards [in context to the English language],” SILDI Student, Juliya Valdez explained when talking about syntax and comparing it to English grammatical structures. “Ute is a language of feeling. I have learned that Ute has to come from you.”

Some of the major challenges included the difference in dialects between the Ute tribes to the pronunciation of words, syntax, and use of the glottal in the language. An understanding occurred within the group to ensure all dialects of the Ute language were respected.

“Knowing that every dialect counts, the sister tribes, and everyone that was in our group, we said, ‘We need to honor that,’” SILDI Student and SUIMA Principal Mari Jo Owens said. Owens explained that within the class she became more comfortable with speaking the language and being more confident and using the language.

“It has brought us all together. I look forward to delivering what I have learned to the community,” Southern Ute Education Dept. Director and SILDI student, LaTitia Taylor said. “It’s going to make us a stronger community.”

Revitalizing the Ute language

“We [Fort Lewis College] are going through a reconciliation process,” said Dr. Jenni Trujillo, Dean of the School of Education at Fort Lewis College. “We know, having been an Indian Boarding School, that languages were stripped and stolen, and so we feel we have a responsibility to do what we can educationally to revitalize and preserve the language.” Trujillo explained further that the work with culture and language reclamation is being led by individual tribes and similar programs to SILDI. Fort Lewis will continue to help with recognition of Tribes and accreditation of programs.

Historically, Fort Lewis Boarding School was one of the many federally recognized boarding schools in the Southwest designed to strip indigenous children of their culture and language through education starting in the late 1800s. The Southern Ute and Ute Mountain Ute bands were one of many tribes educated within the walls of the former military base. The reversal on the impact and historical trauma proliferating within the boarding school era has begun to pick up momentum as many tribes, including the Southern Ute Tribe, are losing many of their fluent elders. Currently, it is estimated that around 20 fluent Ute speakers remain within the Southern Ute Tribe.

“Every time we lose an elder who speaks Ute fluently, it gets a little scarier,” Blue Star said. “Hopefully, we can get to our kids here and make [cultural and language learning] happen.”

With the uncertainty around the loss of language, federal programs and nonprofit organizations have pushed for more support for language revitalization efforts for tribes through the introduction of grants and programs like the Administration for Native Americans (ANA) Preservation and Maintenance grant, and the Northwest Indian Language Institute (NILI) in the Pacific Northwest which holds a similar mission to SILDI for the Southwest.

For the Southern Ute Indian Tribe, Ute language and culture classes are being taught by both tribal departments and elders which are allowing younger generations to learn traditional crafts, making regalia, and cultural traditions and ceremony, in addition to Ute language.

“There is a balance happening within our community and the pressure isn’t on a handful of people,” Blue Star said.

Those within the SILDI class also learned about the importance of language revitalization and how other tribes are overcoming having their language be “asleep.”

“Throughout the whole three years, we learned about these other tribes where their languages were dying and that gave me a better understanding,” Taylor said. “People were unsure and scared about it. Is Ute language going to survive?”

Fort Lewis College will continue to support the Southern Ute Tribe and other tribes during their reconciliation process to help tribes retain their language and cultural practices.

“Preserving and maintaining language once revitalized is always an ongoing process.” Dr. Trujillo said. “There’s been endeavors in this community before, so we are just building on things that have been started. I personally believe that teaching makes a big difference.” According to Dr. Trujillo, SILDI is one step to doing just that by also maintaining a strong connection with the Ute tribes to provide a place for the cultural celebration and learning of Indigenous tribes.

“This was an ambitious program and the fact that it was fulfilled leads us to more exciting opportunities,” Dr. Trujillo stated. “I am really grateful that Fort Lewis got to be a partner in this. We feel an institutional connection that is important.”

The next steps

After finishing the program, many students of SILDI hope to continue their learning of the Ute language and using their certificate with hopes that the program continues through future endeavors, like teaching classes in local schools. Many students, like Juliya Valdez, hope that an immersion program is on the horizon with hopes for a similar program to continue to help certify more Ute language teachers.

For those in the education field, like Owens and Blue Star, SILDI has allowed for a stronger foundation for teaching the Ute language which has helped younger generations learn the Ute language and implement it into the school curriculum. Many SUIMA students have gone as far as creating a short story entirely in Ute or translating an existing story into Ute. A feat unseen in previous classes. It has also instilled more confidence in students and teachers alike, those learning and speaking the Ute language.

“To help the language grow to stay revitalized, we as the [teachers] need to be the role models,” SUIMA principal Mari Jo Owens said. “I think we were doing very well at the beginning of the school year. We came energized (with the language), and we had a lot of staff members grow.”

For the Culture Department, the next step is the introduction of a Ute language app for tablets and smartphones that is specific to the Southern Ute dialect later this year. The project has been funded as part of the same grant as SILDI and aims to create a database for the Ute language and both establish a Ute Language Division and Ute Language Committee.

“Creating the language database, not just the app, is more for the contemporary,” Culture Department Director, Crystal Rizzo explained. “I think establishing a Ute Language Division will help us be able to create realistic goals for that [project].”

Izabella Cloud hopes to use the Ute language as a foundational grounding for the future but also sees language reclamation as a beautiful step for the future of the Southern Ute Tribe.

“When I hear Ute it’s kind of like puzzle pieces that fit together,” Cloud explained. “It makes connections in my brain. I see this as one of my foundation pieces that support me in my future as an elder.”